|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2001 Huyana Potosi and Condoriri Expedition

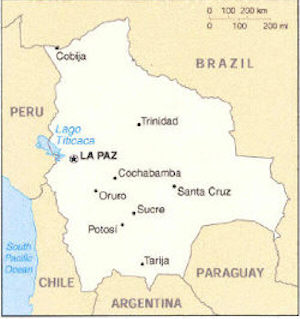

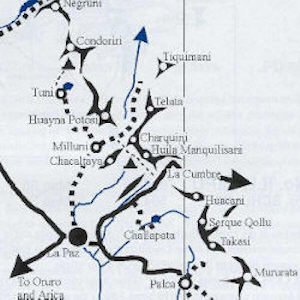

OverviewThe following narrative details our 2001 two-week expedition to the Andes of Bolivia, from preparation at home, through three high altitude climbs, and our return. We successfully summitted 19,974 foot Huyana Potosi, a climb memorable as much for its altitude as the endless night spent at the 18,800 foot high Argentine Camp the night before the summit climb. Then we moved on to the incredibly beautiful Condoriri cirque, northeast of La Paz, and climbed 17,618 foot Pequeno Alpamayo and 17,159 foot Pyramida Blanca. Preparation – April through July

The idea of a climbing trip to Bolivia developed after a chance meeting in Estes Park, Colorado. I was taking a backcountry avalanche course and while killing time before the start of the course, I noted the arrival of another pickup with Wyoming tags. For those not familiar with southeast Wyoming, it is fin fur and feathers country, meaning the odds of meeting another climber from Cheyenne are near zero. I introduced myself and conversation soon led to stories of past climbs and future plans; spring snow climbs in Colorado and a possible summer high altitude trip to South America.

A few weeks later, Gary and I failed in a winter attempt of Medicine Bow Peak, west of Laramie, Wyoming but later in the spring, we made successful snow climbs of Mt. Columbia, Little Bear, and Crestone Peak. These climbs added new Colorado 14'ers to our tallies and gave us the opportunity to start getting into decent shape and brushing up on our snow climbing techniques. In the early summer after the Snowy Range road was re-opened, we also had the opportunity to climb the steep slopes of Medicine Bow Peak, practicing roped pair work, using protection for higher angle snow climbs, and refreshing our ice axe arrest techniques. We also finalized plans for a high altitude adventure in South America and soon settled on Bolivia, based upon the intermediate difficulty of the climbs and seasonal weather constraints. A number of organizations provide guided trips to Bolivia, however we chose to go with the Colorado Mountain School (CMS) due to their geographic proximity to Cheyenne and the quality of their earlier avalanche course. We primarily looked at the guided trip option as a means of familiarizing ourselves with Bolivia while gaining enough climbing experience to later return to a high altitude glaciated peak without a guide.

We redoubled our efforts to get into physical shape in preparation for the promised long days on the high mountains. By mid March, I had begun training on the steps of the football stadium in Laramie, Wyoming, carrying loads up to 40 lbs three days per week. Both of us also did training hikes in the hills between Laramie and Cheyenne and climbed 14'ers in Colorado to gain any possible altitude advantage. In addition, a physical was in order and both of us got shots for tetanus, hepatitis A, and typhoid. We also procured prescriptions for a number of drugs that might be needed in the event of an emergency far removed from medical care. Before we realized it, the end of July had arrived and we were off to Bolivia and for me, the unknowns of high altitude mountaineering.

Denver to La Paz – July 26Diana delivered us to the Denver Airport by mid afternoon and we checked in for the flight to La Paz, via Miami. La Paz is served by multiple airlines but only American flies non-stop from the U.S. so that was our carrier of choice. The flight out was uneventful and after a layover in Miami, we took our connecting flight to La Paz, crossing the Caribbean, the jungles of the Amazon, and the Equator during the night.

The itinerary for the trip called for the early morning arrival in La Paz with the rest of the day wide open for recovering from the overnight flight. A day trip to Lake Titicaca was planned for the next day, followed by the climbing portion of the expedition. The climbing would be split into two parts, the first consisting of a climb of Huyana Potosi, followed by a climb of Illimani. The first climb would begin at the Zongo Dam hut/refugio, at the base of Huyana Potosi, from which two days would be spent on the toe of the nearby glacier, practicing climbing skills and getting further acclimatized. Then, we would climb Huyana Potosi, spending the first night on the glacier at a flat known as the Argentine Camp. The next morning, we would leave camp at 3 a.m. and head for the summit. After summitting, or attempting to do so, we would return to the Argentine Camp, strike the tents, pack up gear and then head on down to the refugio. With luck, transport would arrive and we would spend the night back down in La Paz. That would complete the first climb and first half of the trip.

The second part of the climb would start after a rest day in La Paz. We would head southeast of the city and attempt an ascent of Illimani, a higher peak that would also require at least one overnight on the glacier to reach the summit. Three days were planned for the climb after which we would head back to La Paz, rest a day, and then head home. We also had a wildcard to deal with for the entirety of the trip, namely the possibility that the local political situation would preclude one or both of the climbs planned. For those unfamiliar with Bolivian politics, they have a knack for changing governments quite often and the longevity of the group in power seems often to depend on their ability to convince the rural populace that the government will do something different from the last group in power. The cycle seemed to be threatening to culminate during our trip as evidenced by trenches and stone barricades being constructed to block the flow of commerce, specifically food and other goods into La Paz. The prior group needed to maneuver around barricades on their return to La Paz and some other climbers related being asked to contribute to a campesino group in order to return to La Paz. Of course, we knew none of this upon our arrival but I do not think it would have made much difference to any of us.

Arrival in La Paz – July 27

The inbound flight arrives in La Paz in the early morning, most likely due to the physics of putting a loaded jet on a runway whose elevation is 14,000 feet. Our 767 came in just before dawn and made a wide circular approach to the airport, located in El Alto, an outlying portion of La Paz. We claimed our gear and uneventfully passed through Bolivian immigration and customs, exiting the international section to find the driver CMS had waiting to take us to the hotel in town. The airport in El Alto sits on the altiplano above La Paz proper, the high plateau upon which both Lake Titicaca and the ranges of the Andes are located. Our cab was typical of Latin America and as I chose to sit in the front seat, I was placed in charge of defrosting the driver’s windshield with a damp roll of toilet paper as we cruised the serpentine four-lane spiralling down into La Paz proper. We passed through the main business section of town at about the 13,000 foot mark and kept descending through the myriad of narrow streets lined alternatively with modern buildings and older structures, dating back hundreds of years.

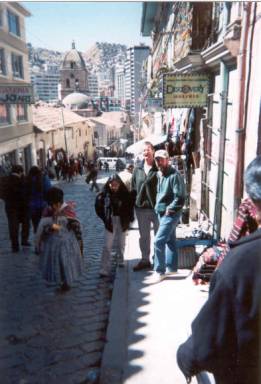

We arrived at the Hotel Calacoto in the lower outskirts of the city and after some initial confusion, mostly language based; we obtained a room and took a brief nap. Soon came a knock at our door and we met Dan, who had been in Bolivia for the summer and would be our guide for the next two weeks of climbing. Dan mentioned that Jim, another climber was already in town, and Anne, the last member of our group, would arrive later in the evening. We made plans to get together for dinner and then Gary and I headed out to exchange dollars and find some lunch. La Paz did not prove to be a surprise with regard to poverty or other "expected" norms of a Latin American city, pretty much fitting the bill with regard to street vendors and the like. It was however different in one respect, altitude. The Calacoto district is located at about 12,000 feet and just about anywhere one goes is uphill, seemingly coming or going. Soon we were puffing our way up toward Calacoto's central market area, changing money at a bank, doing a bit of grocery shopping, and sitting down for lunch in a street side café. Fortunately, my Spanish skills were sufficient to accomplish these tasks without too much difficulty. After lunch, we took a taxi to the central and much older part of the city, where the street markets abound and the variety of wares is fascinating to say the least.

I asked the cab driver to drop us off in front of the Cathedral, which sits on the main drag below the government sector on one side and a bristling swath of street markets on the other. The La Paz “witch's market” was our destination as we had read of lucky charms and dried llama fetuses being the mainstay of the vendor's product lines. From in front of the seriously old Spanish cathedral, we found our way up Calle Sagarniga and into the heart of the market. Gary and I both bought a good luck charm but passed on the chance to obtain a lucky llama fetus. For those less interested in witchcraft and more into climbing logistics, Sagarniga also has a concentration of travel organizers, most of whom arrange (or claim to be able to) climbing trips and provide some limited amount of gear should one come up short. Additionally, the standard tourist wares are available all over place, in addition to other expedition needs like fresh food in bulk and of course, coca leaves for those with an early touch of the soroche. We returned to the hotel and met up with Dan and Jim for dinner. We discussed each other's prior climbing experience and found that Jim, an attorney from Guam, had summitted Mt. Kilmanjaro in Kenya, completed multiple adventure races and is an avid ocean paddler. Gary had summitted one of the high volcanoes in Ecuador, Mts. Hood and Rainer in the Cascade Range and multiple 14'ers in Colorado. That left me with a solid background of more than forty spring and summer climbs in Colorado but lacking any higher altitude experience. Introductions were quickly over, after which we were all off by cab to a restaurant up the street and our first Bolivian dinner.

Day Trip to Lake Titicaca – July 28

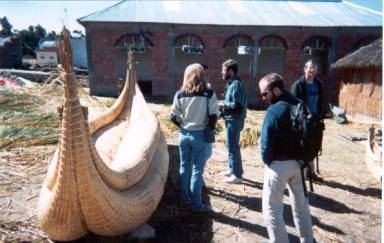

We gathered the next morning for continental breakfast at the hotel and met Anne, who had arrived late the previous evening. Anne is a physician from Sacramento, CA and had summitted Mt. Kilmanjaro and a number of the volcanoes in the Cascade Range. Unfortunately, Anne's luggage did not make the connection leaving the U.S. and she was without gear but hoping it would arrive without too much delay. We made some phone calls to chase the luggage but then were off for the day to Lake Titicaca. The lake trip was part tourism but mostly acclimatization. Anne was fresh from near sea level and Jim was only a few days out of Guam. The lake elevation is about 14,000 feet and a day of walking would help everyone to begin the acclimatization process so critical to later climbing success. We had a hired driver and minibus for the two-hour trip up and out of the canyon La Paz sits in and across the altiplano to the lake. Before setting off across the lake, we had the opportunity to check out the traditional boats, which the lakeside residents construct from dried reeds, and scope out the llama and alpaca wool garb and crafts made by the locals. The quality of these handmade goods is incredible and we all realized that by the end of the trip we would each purchase something to bring home to the wife or for ourselves.

Soon enough, we were off by motor launch, heading for a resort on the shore of the lake about 10 miles or so distant. We had lunch at the hotel, a fish fry for all willing to partake and then we headed back across the lake to the van and La Paz. The view of the mountains forming the eastern edge of the altiplano, stretching from the Cordillera Real near La Paz to the rugged Apolobamba Range to the north, was incredible. For those of us used to the “smaller” 14,000 footers in Colorado, our first glimpse of these big glaciated peaks was impressive to say the least. We arrived back at the hotel in the late afternoon and began what became a daily ritual, the quest for the luggage. Given that Anne had used one airline to get to Lima, Peru and then another to connect to La Paz, the real question soon became, where was the luggage and would her climbing gear ever arrive? Fortunately, she had trip insurance and was therefore able, though not willing, to simply bail and head north.

After completing another series of frustrating luggage calls, we had a group dinner, discussed of the coming climb, and then packed the climbing gear for the next day's ride to the base of Huyana Potosi. We all brought the necessary gear and fortunately, each of us included extra items, all of which went to Anne in a frenzied but successful effort to scrounge sufficient gear to get her climbing, at least during the practice sessions on the toe of the Huyana Potosi glacier. What we were unable to pull together, boots and crampons for example, Dan was able to scrounge from the operator who would provide our transport to and from La Paz. All we could do is hope that the gear would show up, that the driver would check the airport, and that Anne’s duffle would appear at the Huyana Potosi hut before we headed up the mountain. Now throw into that combination the fact that we were in Bolivia . . .

|