|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2001 Huyana Potosi and Condoriri Expedition

Huyana Potosi Base Camp – July 29

The departure from La Paz to the hut below Huyana Potosi was complicated by the still missing luggage. Last minute phone calls and a stop at the airport failed to yield even the slightest indication of a potential positive outcome to the quest for the absent gear. Dan was able to scrounge a set of double boots, crampons, and an axe, and with the addition of our extras; we were off to the mountain by noon. The outfit providing our transportation and operating the refugio said they would check the airport the next two mornings on the off chance the gear made an appearance but given the degree of airline organization seen so far, we knew the odds were against us. However, unknown to us, there was another, more powerful force at work . . . Anne’s dad.

The route to the Huyana Potosi refugio winds up through the narrow streets of La Paz, departing the four lane just a few hairpins below the canyon rim near the airport. From there, it was rough single lane, first with some evidence of paving in the past and then just a single track winding up into the highlands above the city. For me, the ride in itself was a new personal altitude record as before we even reached the flats from which Huyana Potosi was visible we were tearing along at 15,000 feet. One must bear in mind that driving in Bolivia is an expression of machismo, even as in this case when the driver is not a man. To slow down for a curve atop a precipice or make any effort to salvage but one more potential mile from the admittedly rugged suspension of a Toyota Land Cruiser is a sign of weakness. The road topped out and we saw Huyana Potosi, Illimani and other peaks of the Cordillera Real.

We drove further on the dirt track, at a high rate of speed, until we reached the military checkpoint at the ruins of a tin mine. The cemetery just before the mine provided proof positive of Bolivia's past labor strife as the graves were those of miners killed, not by their labors underground, but as they left the mine during a particularly violent strike. The graveyard is unlike anything in the U.S. in that each grave is above the ground and composed of a shelter into which a wooden tray of sorts rests, supporting the bones of the dead.

The owners of the refugio provided both shelter and meals for the daily $10 charge. Breakfast and dinner are served hot and the portions are in keeping with the degree of hunger one will experience in preparing for a climb or after returning from one. The fare is definitely Bolivian but with a touch of weird here and there. For example, each meal started with soup and the potato soup was not made with potato chunks but with frozen French fries. No problem as every meal was well prepared, even if occasionally on the bizarre side. Before heading for bed, we filled water bottles and used the toilet, making sure to do so before the entire water system froze for the night. After that, it was take your chances with the hut's cistern and flushing the toilet with a slosh of water from a 5 gallon bucket, making sure not to drown the rat that lived behind the can! Practice on the Glacier – July 30After an eight o'clock breakfast, everyone but Anne packed their axes and crampons and headed back to the toe of the glacier for the first of two days of practice and acclimatization. Anne hung out at the hut, having picked up a bug of some sort shortly after her arrival in Bolivia. She greeted this morning by puking on Dan's gear from the top bunk of a three-tier bunk bed. We left her with water bottles of Gatorade and our wishes for improved health.

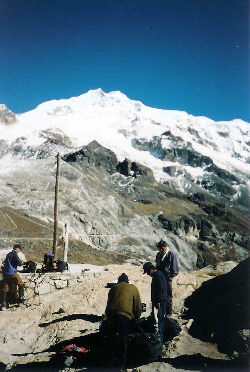

The hike up to the glacier gains about 800 feet over a mile or so, crossing the crest of the concrete dam, following an aqueduct, and then climbing up the terminal moraine to a silty frozen pond below the glacier's terminus. The first day was spent practicing cramponing techniques and then rigging crevasse rescue pulley systems. Each of us made sure we could rig a Z-pulley haulage system without the assistance of the others in the event we were the part of the rope that did not take a crevasse fall. Dan also introduced us to building an V thread ice anchor by threading a cord through two intersecting ice screw holes after which everyone ensured that they could construct balanced anchors using threads and other already familiar anchor systems. We certainly did not intend to lose anyone into a crevasse but everyone did need and wanted to be proficient in the event someone did take an unanticipated fall. More Practice on the Glacier – July 31Anne joined us for the second day of practice on the glacier toe and most of the focus was cramponing on steep ice, roped belay techniques, ice protection installation, rope coils and some two tool front pointing. By the end of the afternoon, everyone was ready and excited about the next day’s climb when we would head up the Huyana Potosi glacier and camp at the "Argentine Camp" located at about elevation 18,000 feet. Base to Argentine Camp – August 1

After breakfast, the porters arrived and re-packed our group gear to their liking. We also met Daniel, a Bolivian guide Dan had hired to break our group into two three-person rope teams. Gary and I would climb with Daniel while Jim and Anne would go with Dan. My Spanish would have to do for the climb, as Daniel's English was minimal.

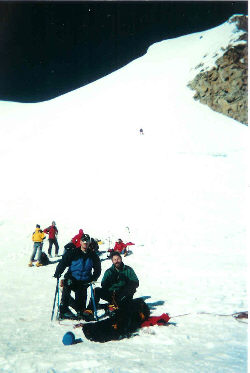

After climbing the switchbacks, we were on snow, skirting the edge of the glacier for a bit before formally stepping back onto the ice for the remainder of the climb. At about the half waypoint, we stopped to rope up and put on crampons for the rest of the hike up to the Argentine Camp. The trail made a steady ascent and in some places was steep enough to require sidestepping. In addition, those of the group not familiar with the rest step became familiar, and practiced it, from this point on.

The trail continued to ascend, passing the lower camping area adjacent to a buttress of rock. We would thankfully keep moving as the denizens of this camp had not made use of a communal pit and the remnants of that decision were scattered about, slowly melting their way into the oblivion of the glacier or being exposed by the sun where previously covered by snow. After the rock camp, the expanse of snow was unbroken but for passing one particularly gaping crevasse. The trail wound its way up the glacier and we made the flat spot known as the Argentine Camp at about three in the afternoon. We were the first to arrive that afternoon and immediately started flattening spots for the tents and digging a shallow pit into which the stoves could be placed out of the wind. Wands were placed to denote the no rope needed safety zone around the tents (crevasses) and everyone noted the location of the pit toilet, i.e. a 4’ x 4’ cutout in a snow bank suitable for #’s 1 and 2. By four, other parties had arrived, including our porters who dropped the group gear. The fact that this was going to become one very cold place when the sun dipped below a distant ridge was not lost on us and we made sure that the sleeping bags were soon lofting, and snow melting on the stoves for water and dinner. Needless to say, at 18,000 feet, there is no running water; therefore, every ounce is melted snow.

By 4:30, the sun was about to drop below a far ridge and the reality of cold, serious cold, entered the group's consciousness. Though the glacier is just about tee shirt country in the sun, it is seven layer turf 30 seconds after the sun is blocked. Everyone layered up and sure enough, the temperature bottomed within seconds of the sun's departure. Brave attempts were made by all to remain outside of the tents and engage in conversation, but nobody lasted more than a few minutes before seeking the warmth of a sleeping bag. Argentine Camp to Huyana Potosi Summit – August 2

Summit day began with a 3 a.m. wake-up and a quick breakfast of oatmeal heavily laced with brown sugar. The boot liners came out of the sleeping bags and cold remained the governing theme. Most of the group started with long underwear, fleece, down, and wind shell layers before later shedding layers on the way to the summit. After breakfast was choked down, everyone emerged into the darkness and rigged the harnesses and ropes for travel across the glacier. We split into two rope teams; Gary and I again were with Daniel as we left camp just a few minutes before the second rope of Jim, Anne and Dan.

An hour later, we were at the base of the bergshrund marking the top of the lower glacier. This large crevasse, formed where the glacier has pulled away from the valley headwall, required about a 120-foot climb up ice and snow at an inclination of about 70 degrees. Daniel climbed first and set up a belay for Gary and me to follow. The route had seen a lot of travel so rather than being faced with a sheer face, we scrambled up the trough cut into the ice by the ascents and descents of many a party before us. At the top of the ice wall, we re-spaced on the rope and set off up the ridgeline leading ever upward toward the summit. By this time, day dawned over the Amazon Basin, very much lower and to the east; however, it was still cold enough to keep the shell zipped and the heaviest BD gloves on the hands.

The route up the ridge alternated between sections steep enough to require a bit of side stepping and more tame sections where the going would have been monotonous but for the views off toward the east, the sun rising steadily over the jungles far below. Our team made good time, passing a number of slower Euro ropes as well as a few gaping crevasses before arriving at the flats that form the base of the summit pyramid.

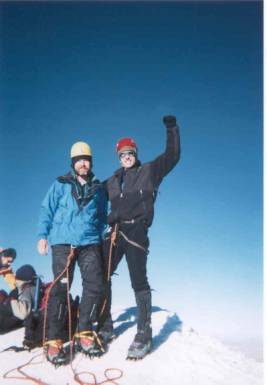

Daniel gave us a choice between a direct climb toward the summit versus a more circular route that gained the summit via a knife-edge ridge. We chose the ridge primarily for the experience of movement along an exposed ridge as compared to a simpler but more steep and straightforward snow climb. Our experience in Colorado had provided plenty of climbs right up the middle of a slope or couloir but no opportunity to move along a knife-edge with a touch of exposure to keep one’s attention tuned to the task. We made the ridge after another half hour and with Daniel on belay; we made our way up the knife-edge. The exposure to the north was about 3000 feet whereas the southern edge was a more tame 500 to 800 feet. We traversed along the southern side and after a steep pitch or two, made the summit at about eight in the morning. Overall, we felt good and took in the sights from this lofty 20,000-foot high perch.

The altitude of the Huyana Potosi summit was 6000 feet higher than any other point I had achieved in my previous climbing experience. The air was thin to say the least but we found that as long as quick steps were avoided, both Gary and I remained clear-headed and steady on the feet. We took some summit photos and headed back down the ridge that we had ascended just one half hour earlier. We had been lucky; the weather was picture postcard Bolivian winter, cold, dead still and clear.

The trip down to Argentine camp was fast and warm in the now bright sunlight. We easily descended the undulating ridge, passing crevasses unseen in the darkness of our ascent, before reaching the top of the bergshrund. Daniel rigged a belay and we down climbed the steep chute to the flat below. We now had only to cross the top of the lower glacier, so once again we roped up and stepped our way on back to the tents by just after 11 that morning. Our climb to nearly 20,000 feet had been a success and taken only seven hours in the process.

Jim and Anne caught up with us on the way down and we arrived together at the hut, tired but satisfied with the results of our two-day climb. To a person we were anxiously looking forward to the comforts of La Paz and a well deserved in town meal. Transportation back to La Paz was to arrive in an hour, so we spent a few minutes speed packing our remaining gear in the hut and sitting down for some tea. I took this opportunity to try the local tea variety, coca tea. It is prepared by covering the bottom of a coffee mug with whole coca leaves and adding hot water, allowing it to steep for a few minutes before drinking. Coca tea and coca leaves are part of the Bolivian culture and have been used for years for the relief of the soroche, or altitude sickness. I did not detect any major effects but figured the experience to be a harmless part of the Bolivian climbing experience.

Our transportation arrived as planned and before leaving the hut, we took care of the tips for the cook, guide, and porters, each of who had been great and contributed to our success on Huyana Potosi. Two hours later we were back in Calacoto, thinking about a hot shower and the possibility that the off and on banter about a llama steak might become reality before the close of the evening meal. Also, we were now at the paltry altitude of 12,000 feet . . . no Cheynes-Stokes tonight! Rest day in La Paz – August 3

Dan needed the day to line up the remainder of the trip, which was to prove very different from the plans made before coming to Bolivia. Our original plan was to climb Huyana Potosi and then move onto the even higher Illimani. However, we talked with a group out of Pennsylvania who had been to an area called Condoriri instead of Illimani and they had had a good time. Both the Pennsylvanians and Dan told of this glacial cirque and the half dozen or so peaks ranging from 17,000 to 18,500 feet that were accessible from a central campsite. We came to a unanimous decision to forgo the higher altitude and cold glacier camps needed to do a climb of Illimani and instead set up a more temperate base camp in the Condoriri cirque, located at a pleasant 15,000 feet.

|