|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Chopicalqui - Millisraju ExpeditionChopicalqui High Camp

July 8, 2005 – Move from Chopi Moraine Camp to Chopi High Camp

The move from the Chopi moraine camp to the high camp would take us from about 16,500 feet to about 18,200 feet and put us in position to take a shot at the 20,800-foot summit (map). We did not need to get an extra early start but we did want to get onto the glacier while the snow bridges across the crevasses were still solid and before the sun was dialed all the way up to broil. We planned to travel as light as possible, our glacier travel gear in use and the food and two light mountaineering tents split up amongst Joaquin, G and myself. Elias served a light breakfast and we coordinated the radio schedule we would use to communicate between the high camp and the moraine camp. We took Motorola “talk-about” radios with us on the Pisco climb and they would have been great for letting Elias know our progress . . . but for the fact that we did not have a defined communications plan. We ended up talking sporadically but this time we planned to do better.

We left for the high camp at about 9:30 in the morning and traversed around the other camp pads and up onto the last bit of moraine leading to the toe of the glacier. Whenever I say moraine, just think steep trail and scree under foot, which says it all if you are not sweating the elevation. Add in the elevation factor and you can just substitute the word . . . miserable. The route just beyond the moraine camp certainly classifies as such as the trail climbs steeply up a braided section of switchbacks laden with loose rock. It is a testing ground for hiking poles and God help those who do not have poles or a well-tuned sense of balance. Honestly, the pitch really is not that high or long, it is just a trying start. Once above the first pitch, the trail wanders upward at a lesser grade to the toe of the glacier, where there is a flat spot to drop packs and lay out the ropes and other gear needed for travel up the glacier.

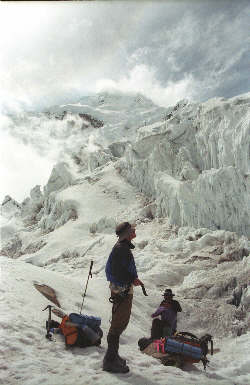

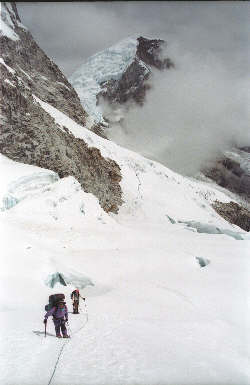

We set up a three-person rope team with Gary in the lead, Joaquin in the center and me on the tail, doing the photo gig. There was a short steep pitch onto the glacier proper and we followed the trail made by many preceding parties that wound its way upward, left, right, and so on as crevasses were encountered. The grade is not tame, flats followed by short steep rolls to the next flat. The crevasses were all negotiated on snow bridges, and although some bridges were a bit on the narrow side, the spans were limited in every case. There was of course a nice selection of gaping maws to keep one’s attention focused. Overall, the route up the glacier was straightforward and well traveled by many other parties.

We made good progress up the slopes as the sun began to beat down upon us. We hesitated to stop on the lowest 1/3 of the route due to the proximity of a rock wall that according to Joaquin tended to shed rock once it warmed up. The sun was already on the rock wall so we kept moving. After we covered the first third, our pace slowed a bit and I took time to take some photos and we stopped to drink and eat here and there. The trail continued steadily upward until just beyond the 2/3 mark when the route begins a traverse to the left in the direction of the summit. The summit would not come this day but we were now at least pointing in that direction. We continued upward, now climbing more sustained slopes until we arrived at a flat area that Joaquin noted was just prior to the high camp. We knew we were really close when Joaquin unclipped and walked over the crest to claim a leveled tent pad previously vacated by another party.

We were the second group to arrive at the Col camp so there was no shortage of tent pads cut out left by previous groups over the past couple of weeks. We pounded a couple of pickets into the snowy slope and tied our packs to the anchors. I had crampons on and I was not worried about taking a slider on the relatively tame slope but the thought of a pack taking a terminal ride was not my idea of fun. The tents were soon pitched and we killed the remainder of the afternoon sitting in the sun, taking in the ultra-violet warmth. Col Camp cooking was a non-gourmet affair as Elias dispatched us with freeze-dried rations sans pressure cooker. Between the three of us, we managed to put down two of them before the sunset and we moved to the sleeping bags for an all too short night. Our summit bid would start with a 1 a.m. wakeup and 2 a.m. departure. Though we were in the bags by 6 p.m., I knew from the Argentine Camp on Huyana Potosi little sleep would follow at this rarified elevation.

Early on July 9, 2005 – Summit Bid and Failure I’ve made a habit with this web site of generally telling it like it was, even though I run the risk of looking like an idiot in the process. I’ll be honest, we’re a couple of guys from Wyoming who love to climb and have aspirations to pull off a 6000 meter peak without having too much of a helping hand. My experience on July 8 was a reminder that if you are going to lose body parts before a climbing trip, don’t do it just 8 weeks before you try to pull off that 6000-meter goal. You might have a day like I did. The alarm went off at 1 a.m. and it could not have come soon enough. I had been “practicing” the on and off Cheyne Stokes breathing method for about 6 hours and I was looking forward to giving up any further attempts to sleep. The alarm rang and from Gary’s tent came his call that it was in fact one in the morning. For those who have not often slept at 18k my description of getting one’s gear together and clothes on comes simply as repeat of your own experience. For those who have never enjoyed the experience, gearing up is a repetition of individual tasks separated by the opportunity to stop for a pause and a few breaths of air. I got my gear on and exited the tent. We were the first group up. Gary was up and ready as well and began laying the rope out into which we would both tie in for the trip to the summit. He quickly coiled his extra rope in around his torso and I began to make a similar effort. The coils went around fine but the knot bringing the whole arrangement together did not come. I tried once, twice, three times, but I simply could not tie the knot that I had tied without effort at the toe of the glacier sixteen hours before. I called to Gary to give me a hand and he quickly fashioned the required knot. We were off to a slow start but at least we were summit bound. The route above the camp is also obvious due to the travels of prior climbers; we took to the trail heading up. We went perhaps 100 vertical feet and stopped. Gary turned and asked me how I was doing and my response was not immediately forthcoming. Here we were, at 18,200 feet in Peru, having traveled 3000 miles from home and having spent for than a few dollars in the process, and I cannot get my shit together. I voiced that I would be fine and that we should continue climbing. We climbed another 100 feet and again stopped. I was simply not home . . . there was nobody home. Gary and I have climbed together in Colorado, Canada, Bolivia, and Peru and we can pretty much read each other’s abilities and physical state. That morning my state was an easy read and the indicator was reading bone dry empty. We turned the climb and our shot at this 6000-meter peak was over. Climbing is tough enough as it is; however when climbing in a team there is a great desire not to disappoint the other members of the team. One can often tough it out through a particularly bad day or convince oneself that all will be well once the sun breaks the horizon, the cold of night fades, and new found warmth tells the body that the worst is over. This was not one of those days as my mind was simply not able to process the efforts needed to continue the climb. I was spent. As my ability failed me, Gary’s character came forth to demonstrate what a true climbing partner and friend he is. He turned around on a dream climb and let the obvious disappointment take a back seat to what was the best course of action. Of course, we still had half a trip left and the prospect of another big mountain but turning around at the very start of the summit day is no easy task. However, regardless of the disappointment he may have felt, his kind “Its OK” said it all and allowed me to weather my disappointment without further embarrassment. We went to the tents for some sleep and a descent to the Moraine Camp in the morning.

|