Climbing Pequeno Alpamayo

Pequeno Alpamayo serves up the blue ice special . . .

The alarm was set for 2 a.m. and we were both psyched for the climb of Pequeno Alpamayo. We had both done the climb before, in 2001, as part of our first trip to South America. We had been guided on that climb and since them we wanted to repeat this climb without a helping hand. We were both feeling a bit on the weaker side but figured that if we took it slow and easy, we'd do fine. The alarm was set for 2 a.m. and we were both psyched for the climb of Pequeno Alpamayo. We had both done the climb before, in 2001, as part of our first trip to South America. We had been guided on that climb and since them we wanted to repeat this climb without a helping hand. We were both feeling a bit on the weaker side but figured that if we took it slow and easy, we'd do fine.

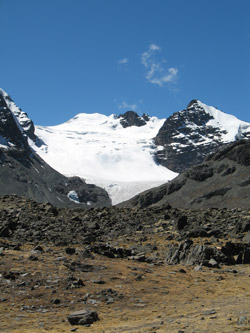

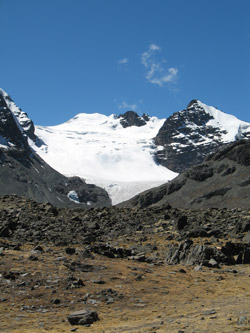

The route up Pequeno Alpamayo leaves the Lago Chiar Kota camp and follows the valley further up to the toe of the large glacier that has been visible since the approach hike to camp. The summit of Pequeno Alpamayo is visible from the camp but not by much as the flank of Tarija, an intermediate peak, obscures all but the top of the peak. The route up Pequeno Alpamayo leaves the Lago Chiar Kota camp and follows the valley further up to the toe of the large glacier that has been visible since the approach hike to camp. The summit of Pequeno Alpamayo is visible from the camp but not by much as the flank of Tarija, an intermediate peak, obscures all but the top of the peak.

We headed up valley in the dark and managed to lose the trail as it crossed the boggy ground in and around the sedimented lake about 1/3 of the way up to the glacier. He split and G caught the trail first, calling me toward him, after which we were on route all the way to the toe of the glacier. As we approached the ice, the air grew markedly colder, leaving no doubt that the lighter mass looming ahead was the glacier. We stopped at the base, added a layer of down, and gathered the gear we would need for the climb. We were both going as light as possible, mostly food and glacier travel gear and one more layer, just in case. We geared up, shot a Goo and put a few more Gu's into accessible pockets to keep them warm to avoid shucking a pack for them along the way. We headed up valley in the dark and managed to lose the trail as it crossed the boggy ground in and around the sedimented lake about 1/3 of the way up to the glacier. He split and G caught the trail first, calling me toward him, after which we were on route all the way to the toe of the glacier. As we approached the ice, the air grew markedly colder, leaving no doubt that the lighter mass looming ahead was the glacier. We stopped at the base, added a layer of down, and gathered the gear we would need for the climb. We were both going as light as possible, mostly food and glacier travel gear and one more layer, just in case. We geared up, shot a Goo and put a few more Gu's into accessible pockets to keep them warm to avoid shucking a pack for them along the way.

We knew from our previous practice session on the glacier that there was a herd path beaten up the neve portion of the glacier that started above the bare ice zone that extended perhaps a quarter mile up the ice. I took the lead as I was the elected pace setter and my glacier travel pace is slower than G's. G was feeling the previous day and we had decided on my slower pace, at least until the sun came up and the solar Prozac that drives me during the daylight hours kicked in. I started the climb slowly and we soon crested the steep section and then trended to the left to pick up the herd path. We knew from the previous recon that there was not much in the way of crevasses down low, just some very narrow transverse cracks mostly filled in by frozen melt from above. G spotted the herd path before I did and we took that route on upward. We knew from our previous practice session on the glacier that there was a herd path beaten up the neve portion of the glacier that started above the bare ice zone that extended perhaps a quarter mile up the ice. I took the lead as I was the elected pace setter and my glacier travel pace is slower than G's. G was feeling the previous day and we had decided on my slower pace, at least until the sun came up and the solar Prozac that drives me during the daylight hours kicked in. I started the climb slowly and we soon crested the steep section and then trended to the left to pick up the herd path. We knew from the previous recon that there was not much in the way of crevasses down low, just some very narrow transverse cracks mostly filled in by frozen melt from above. G spotted the herd path before I did and we took that route on upward.

The climb of the glacier leading toward Tarija is a matter of climbing a couple of steep rolls separated by flatter stretches. I've not found any of it so steep as to require any front point actions whatsoever and very little side stepping, even though I tend to head for those moves when given the opportunity. We climbed perhaps half way up the long slope before G let me know that he was cold and wanted to swap the lead to warm up. I was fine with that though I was starting to get that magical feeling in my bowels that told me today would be another day like the day before and the day before that. We pinwheeled and G took the lead, nary losing but a moment of our upward progress. The climb of the glacier leading toward Tarija is a matter of climbing a couple of steep rolls separated by flatter stretches. I've not found any of it so steep as to require any front point actions whatsoever and very little side stepping, even though I tend to head for those moves when given the opportunity. We climbed perhaps half way up the long slope before G let me know that he was cold and wanted to swap the lead to warm up. I was fine with that though I was starting to get that magical feeling in my bowels that told me today would be another day like the day before and the day before that. We pinwheeled and G took the lead, nary losing but a moment of our upward progress.

As we neared the top of the final roll, the moment arrived and I called for G to stop. He wanted to top the roll but nature said no and instead I asked him to drop the roll of paper and climb a rope length for me to recover it. Time was slipping by quickly. I tell this part of the climb as it is part of climbing, the true misery of climbing if you are sick or you might get sick. The human side of the activity and what we ought to just admit is a bit risque but within the realm of inquiry by all those who have given alpine climbing some thought. I'm now plunging my ice axe into the snow on a 30 degree snow slope and struggling to extract myself from my harness without coming off the rope. I get out of the belt loops fine and the waist is still securing me to the rope but time is running out. Got to get those pants down, I mean now, and I did just at the last moment. I fell forward onto my knees and . . . As we neared the top of the final roll, the moment arrived and I called for G to stop. He wanted to top the roll but nature said no and instead I asked him to drop the roll of paper and climb a rope length for me to recover it. Time was slipping by quickly. I tell this part of the climb as it is part of climbing, the true misery of climbing if you are sick or you might get sick. The human side of the activity and what we ought to just admit is a bit risque but within the realm of inquiry by all those who have given alpine climbing some thought. I'm now plunging my ice axe into the snow on a 30 degree snow slope and struggling to extract myself from my harness without coming off the rope. I get out of the belt loops fine and the waist is still securing me to the rope but time is running out. Got to get those pants down, I mean now, and I did just at the last moment. I fell forward onto my knees and . . .

Business taken care of, I tidied up a bit and called out to G that I was somewhat worse for wear but that I would be ready to get moving again in just another minute or two. I'm well aware that he is standing still and cooling down, hence I am making an effort to get ready as quickly as possible without dragging me or my gear through, well . . . you get the idea. I was finally ready and we climbed on to the top of the ridge connecting Tarija and the flank of Huayomen. The top of the glacier had a long traversing bergshrund, really more of a ten foot deep snow filled basin and at the far edge, a sing open crevasse of substantial depth. We hopped the gap and looped our way back at the very top to again approach Tarija which we would have to cross to again see Pequeno Alpamayo. The slope of Tarija was sun battered, leaving cupped neve ridges and blades atop a layer of hard blue ice. The crampons bit nicely and there did not seem to be much exposure as a fall would be caught by a ridge or man size wallow, although eh slope is likely 35 to 40 degrees. Business taken care of, I tidied up a bit and called out to G that I was somewhat worse for wear but that I would be ready to get moving again in just another minute or two. I'm well aware that he is standing still and cooling down, hence I am making an effort to get ready as quickly as possible without dragging me or my gear through, well . . . you get the idea. I was finally ready and we climbed on to the top of the ridge connecting Tarija and the flank of Huayomen. The top of the glacier had a long traversing bergshrund, really more of a ten foot deep snow filled basin and at the far edge, a sing open crevasse of substantial depth. We hopped the gap and looped our way back at the very top to again approach Tarija which we would have to cross to again see Pequeno Alpamayo. The slope of Tarija was sun battered, leaving cupped neve ridges and blades atop a layer of hard blue ice. The crampons bit nicely and there did not seem to be much exposure as a fall would be caught by a ridge or man size wallow, although eh slope is likely 35 to 40 degrees.

We climbed to the top of the intermediate peak and crossed over another small bergshrund to the proper summit of Tarija. We stopped for a Goo and drink and now, in full sunlight, we looked down the class 4 scramble to the connecting ridge and Pequeno Alpamayo beyond. We knew the route from before and took the opportunity to drop the trekking poles and a few other gear items we knew we would not need. The climb down to the connecting ridge is straight forward and takes perhaps 15 minutes. We were not in a hurry but we did know that there was a group fairly close behind us and we knew we did not want to share the route with or follow another group up the flank of Alpamayo. We bottomed out on the connecting ridge and cut down the the saddle proper before starting back up Alpamayo proper. It looked like the only areas we would need to place any protection would be the last two pitches as the first few steep sections were pretty tame. We climbed to the top of the intermediate peak and crossed over another small bergshrund to the proper summit of Tarija. We stopped for a Goo and drink and now, in full sunlight, we looked down the class 4 scramble to the connecting ridge and Pequeno Alpamayo beyond. We knew the route from before and took the opportunity to drop the trekking poles and a few other gear items we knew we would not need. The climb down to the connecting ridge is straight forward and takes perhaps 15 minutes. We were not in a hurry but we did know that there was a group fairly close behind us and we knew we did not want to share the route with or follow another group up the flank of Alpamayo. We bottomed out on the connecting ridge and cut down the the saddle proper before starting back up Alpamayo proper. It looked like the only areas we would need to place any protection would be the last two pitches as the first few steep sections were pretty tame.

We climbed on an came to the bottom of the second to lat pitch which is the longest and I think the steepest part of the climb. G took the lead as my fecal interlude has taken most of the energy i had to spare. I was climbing and feeling OK but I was not lead material at this point of the climb. We looked at the pitch and G took the pickets and screws, as I would second. We both felt good enough to simul-climb the pitch, not seeing a need to set a formal belay but wanting to have a bit of gear in just in case. G took off, placing a screw down low to protect the base of the climb and then two pickets and another screw toward the top. We found that the neve was thin, real thin, and what lay under it was hard blue ice. We used all the protection we had to clear the top of that slope and really ended up climbing the top quarter with no gear in as I was grabbing the pro as I passed each piece so we could use it again on the next pitch. The top quarter was tamer so neither of us took serious worry over the lack of protection. We climbed on an came to the bottom of the second to lat pitch which is the longest and I think the steepest part of the climb. G took the lead as my fecal interlude has taken most of the energy i had to spare. I was climbing and feeling OK but I was not lead material at this point of the climb. We looked at the pitch and G took the pickets and screws, as I would second. We both felt good enough to simul-climb the pitch, not seeing a need to set a formal belay but wanting to have a bit of gear in just in case. G took off, placing a screw down low to protect the base of the climb and then two pickets and another screw toward the top. We found that the neve was thin, real thin, and what lay under it was hard blue ice. We used all the protection we had to clear the top of that slope and really ended up climbing the top quarter with no gear in as I was grabbing the pro as I passed each piece so we could use it again on the next pitch. The top quarter was tamer so neither of us took serious worry over the lack of protection.

We kept moving and went right into the next pitch, which was a full rope length, shorter than the the rope and half length of the first pitch. G beat his way up this one as well, breaking off dinner plate pieces of blue ice with every stick of his tool. I'm dodging the ice as it come down, learning all too well the moves I had inadvertently taught G on the Silverhorn route of Mount Athabasca in 2002 when we climbed a similar icy slope. The cramponing here is front pointing as the slope was too steep for me to use the french technique that i prefer in all cases. We topped the second slope and walked the final meters to the summit proper. I was beat but we were both on the summit and happy to be there. We kept moving and went right into the next pitch, which was a full rope length, shorter than the the rope and half length of the first pitch. G beat his way up this one as well, breaking off dinner plate pieces of blue ice with every stick of his tool. I'm dodging the ice as it come down, learning all too well the moves I had inadvertently taught G on the Silverhorn route of Mount Athabasca in 2002 when we climbed a similar icy slope. The cramponing here is front pointing as the slope was too steep for me to use the french technique that i prefer in all cases. We topped the second slope and walked the final meters to the summit proper. I was beat but we were both on the summit and happy to be there.

The following party, a gal from Washington State and a Bolivian guide topped out about ten minutes later and we took the obligatory summit shots for each other. I also took the opportunity to duck down the slope and make another deposit, like that was really a surprise. We shot a Goo, ate bit of the bag lunch Mario provided us with and prepared to head down. We figured to rappel the steep slopes, doing the second one in two pitches to land us on the flats at the bottom. We also found that if we trended a bit off to the side of the obvious route the neve was not beat up as badly. We set a picket for the first slope and G rappelled on down and took up a belay stance on the upper flat. i down climbed to him and we walked the lip of the longer pitch, set a picket and rappelled most of the way down. We set a second picket and rappelled and down climbed the bottom half, leaving one picket above for Pachamama or more likely the pair of pretty damn good Italian climbers who ascended past us, un-roped, as we came of the second pitch. The following party, a gal from Washington State and a Bolivian guide topped out about ten minutes later and we took the obligatory summit shots for each other. I also took the opportunity to duck down the slope and make another deposit, like that was really a surprise. We shot a Goo, ate bit of the bag lunch Mario provided us with and prepared to head down. We figured to rappel the steep slopes, doing the second one in two pitches to land us on the flats at the bottom. We also found that if we trended a bit off to the side of the obvious route the neve was not beat up as badly. We set a picket for the first slope and G rappelled on down and took up a belay stance on the upper flat. i down climbed to him and we walked the lip of the longer pitch, set a picket and rappelled most of the way down. We set a second picket and rappelled and down climbed the bottom half, leaving one picket above for Pachamama or more likely the pair of pretty damn good Italian climbers who ascended past us, un-roped, as we came of the second pitch.

We retraced our course across the connecting ridge and tried to make good time as the sun was quickly softening the snow and we wanted to stay ahead of lousy conditions on the main part of the glacier as much as possible. We trudged up the short climb to the base of the rock leading to the summit of Tarija and then climbed to that summit, not bothering to un-rope or drop our crampons. We reclaimed our trekking poles and other left luggage and made our way down the steep face of Tarija to the connecting saddle and circuitous route out and around the bergshrund and sole major crevasse on the whole climb. Then it was down the long slope to the toe of the glacier, a route we made good time on as we wanted to avoid any extended stops below the flank of Huayomen and the possibility of anything sliding from its sun scorched upper snow fields. We retraced our course across the connecting ridge and tried to make good time as the sun was quickly softening the snow and we wanted to stay ahead of lousy conditions on the main part of the glacier as much as possible. We trudged up the short climb to the base of the rock leading to the summit of Tarija and then climbed to that summit, not bothering to un-rope or drop our crampons. We reclaimed our trekking poles and other left luggage and made our way down the steep face of Tarija to the connecting saddle and circuitous route out and around the bergshrund and sole major crevasse on the whole climb. Then it was down the long slope to the toe of the glacier, a route we made good time on as we wanted to avoid any extended stops below the flank of Huayomen and the possibility of anything sliding from its sun scorched upper snow fields.

We landed gently on the rocks at the toe of the glacier and took a well deserved break and bite to eat. We gathered gear and made our way back down the floor of the valley to the camp below and what we knew would be a good dinner by Mario. We discussed the game plan for the rest of the climbing planned for Condoriri and accepted that the climb we had just completed had taken what reserves we had and that the only way we were going to really recover would be to head for La Paz for a few days. Not unheard of as we had crossed paths with other groups who has similar bouts of illness and the need to return to town to recover. After four trips to South America with nothing other than an occasional case of the runs or a chest cold, our time had come and with it our climb to the head of the Condor vanished as well.

|

The alarm was set for 2 a.m. and we were both psyched for the climb of Pequeno Alpamayo. We had both done the climb before, in 2001, as part of our first trip to South America. We had been guided on that climb and since them we wanted to repeat this climb without a helping hand. We were both feeling a bit on the weaker side but figured that if we took it slow and easy, we'd do fine.

The alarm was set for 2 a.m. and we were both psyched for the climb of Pequeno Alpamayo. We had both done the climb before, in 2001, as part of our first trip to South America. We had been guided on that climb and since them we wanted to repeat this climb without a helping hand. We were both feeling a bit on the weaker side but figured that if we took it slow and easy, we'd do fine.  The route up Pequeno Alpamayo leaves the Lago Chiar Kota camp and follows the valley further up to the toe of the large glacier that has been visible since the approach hike to camp. The summit of Pequeno Alpamayo is visible from the camp but not by much as the flank of Tarija, an intermediate peak, obscures all but the top of the peak.

The route up Pequeno Alpamayo leaves the Lago Chiar Kota camp and follows the valley further up to the toe of the large glacier that has been visible since the approach hike to camp. The summit of Pequeno Alpamayo is visible from the camp but not by much as the flank of Tarija, an intermediate peak, obscures all but the top of the peak. We headed up valley in the dark and managed to lose the trail as it crossed the boggy ground in and around the sedimented lake about 1/3 of the way up to the glacier. He split and G caught the trail first, calling me toward him, after which we were on route all the way to the toe of the glacier. As we approached the ice, the air grew markedly colder, leaving no doubt that the lighter mass looming ahead was the glacier. We stopped at the base, added a layer of down, and gathered the gear we would need for the climb. We were both going as light as possible, mostly food and glacier travel gear and one more layer, just in case. We geared up, shot a Goo and put a few more Gu's into accessible pockets to keep them warm to avoid shucking a pack for them along the way.

We headed up valley in the dark and managed to lose the trail as it crossed the boggy ground in and around the sedimented lake about 1/3 of the way up to the glacier. He split and G caught the trail first, calling me toward him, after which we were on route all the way to the toe of the glacier. As we approached the ice, the air grew markedly colder, leaving no doubt that the lighter mass looming ahead was the glacier. We stopped at the base, added a layer of down, and gathered the gear we would need for the climb. We were both going as light as possible, mostly food and glacier travel gear and one more layer, just in case. We geared up, shot a Goo and put a few more Gu's into accessible pockets to keep them warm to avoid shucking a pack for them along the way. We knew from our previous practice session on the glacier that there was a herd path beaten up the neve portion of the glacier that started above the bare ice zone that extended perhaps a quarter mile up the ice. I took the lead as I was the elected pace setter and my glacier travel pace is slower than G's. G was feeling the previous day and we had decided on my slower pace, at least until the sun came up and the solar Prozac that drives me during the daylight hours kicked in. I started the climb slowly and we soon crested the steep section and then trended to the left to pick up the herd path. We knew from the previous recon that there was not much in the way of crevasses down low, just some very narrow transverse cracks mostly filled in by frozen melt from above. G spotted the herd path before I did and we took that route on upward.

We knew from our previous practice session on the glacier that there was a herd path beaten up the neve portion of the glacier that started above the bare ice zone that extended perhaps a quarter mile up the ice. I took the lead as I was the elected pace setter and my glacier travel pace is slower than G's. G was feeling the previous day and we had decided on my slower pace, at least until the sun came up and the solar Prozac that drives me during the daylight hours kicked in. I started the climb slowly and we soon crested the steep section and then trended to the left to pick up the herd path. We knew from the previous recon that there was not much in the way of crevasses down low, just some very narrow transverse cracks mostly filled in by frozen melt from above. G spotted the herd path before I did and we took that route on upward. The climb of the glacier leading toward Tarija is a matter of climbing a couple of steep rolls separated by flatter stretches. I've not found any of it so steep as to require any front point actions whatsoever and very little side stepping, even though I tend to head for those moves when given the opportunity. We climbed perhaps half way up the long slope before G let me know that he was cold and wanted to swap the lead to warm up. I was fine with that though I was starting to get that magical feeling in my bowels that told me today would be another day like the day before and the day before that. We pinwheeled and G took the lead, nary losing but a moment of our upward progress.

The climb of the glacier leading toward Tarija is a matter of climbing a couple of steep rolls separated by flatter stretches. I've not found any of it so steep as to require any front point actions whatsoever and very little side stepping, even though I tend to head for those moves when given the opportunity. We climbed perhaps half way up the long slope before G let me know that he was cold and wanted to swap the lead to warm up. I was fine with that though I was starting to get that magical feeling in my bowels that told me today would be another day like the day before and the day before that. We pinwheeled and G took the lead, nary losing but a moment of our upward progress. As we neared the top of the final roll, the moment arrived and I called for G to stop. He wanted to top the roll but nature said no and instead I asked him to drop the roll of paper and climb a rope length for me to recover it. Time was slipping by quickly. I tell this part of the climb as it is part of climbing, the true misery of climbing if you are sick or you might get sick. The human side of the activity and what we ought to just admit is a bit risque but within the realm of inquiry by all those who have given alpine climbing some thought. I'm now plunging my ice axe into the snow on a 30 degree snow slope and struggling to extract myself from my harness without coming off the rope. I get out of the belt loops fine and the waist is still securing me to the rope but time is running out. Got to get those pants down, I mean now, and I did just at the last moment. I fell forward onto my knees and . . .

As we neared the top of the final roll, the moment arrived and I called for G to stop. He wanted to top the roll but nature said no and instead I asked him to drop the roll of paper and climb a rope length for me to recover it. Time was slipping by quickly. I tell this part of the climb as it is part of climbing, the true misery of climbing if you are sick or you might get sick. The human side of the activity and what we ought to just admit is a bit risque but within the realm of inquiry by all those who have given alpine climbing some thought. I'm now plunging my ice axe into the snow on a 30 degree snow slope and struggling to extract myself from my harness without coming off the rope. I get out of the belt loops fine and the waist is still securing me to the rope but time is running out. Got to get those pants down, I mean now, and I did just at the last moment. I fell forward onto my knees and . . .  Business taken care of, I tidied up a bit and called out to G that I was somewhat worse for wear but that I would be ready to get moving again in just another minute or two. I'm well aware that he is standing still and cooling down, hence I am making an effort to get ready as quickly as possible without dragging me or my gear through, well . . . you get the idea. I was finally ready and we climbed on to the top of the ridge connecting Tarija and the flank of Huayomen. The top of the glacier had a long traversing bergshrund, really more of a ten foot deep snow filled basin and at the far edge, a sing open crevasse of substantial depth. We hopped the gap and looped our way back at the very top to again approach Tarija which we would have to cross to again see Pequeno Alpamayo. The slope of Tarija was sun battered, leaving cupped neve ridges and blades atop a layer of hard blue ice. The crampons bit nicely and there did not seem to be much exposure as a fall would be caught by a ridge or man size wallow, although eh slope is likely 35 to 40 degrees.

Business taken care of, I tidied up a bit and called out to G that I was somewhat worse for wear but that I would be ready to get moving again in just another minute or two. I'm well aware that he is standing still and cooling down, hence I am making an effort to get ready as quickly as possible without dragging me or my gear through, well . . . you get the idea. I was finally ready and we climbed on to the top of the ridge connecting Tarija and the flank of Huayomen. The top of the glacier had a long traversing bergshrund, really more of a ten foot deep snow filled basin and at the far edge, a sing open crevasse of substantial depth. We hopped the gap and looped our way back at the very top to again approach Tarija which we would have to cross to again see Pequeno Alpamayo. The slope of Tarija was sun battered, leaving cupped neve ridges and blades atop a layer of hard blue ice. The crampons bit nicely and there did not seem to be much exposure as a fall would be caught by a ridge or man size wallow, although eh slope is likely 35 to 40 degrees. We climbed to the top of the intermediate peak and crossed over another small bergshrund to the proper summit of Tarija. We stopped for a Goo and drink and now, in full sunlight, we looked down the class 4 scramble to the connecting ridge and Pequeno Alpamayo beyond. We knew the route from before and took the opportunity to drop the trekking poles and a few other gear items we knew we would not need. The climb down to the connecting ridge is straight forward and takes perhaps 15 minutes. We were not in a hurry but we did know that there was a group fairly close behind us and we knew we did not want to share the route with or follow another group up the flank of Alpamayo. We bottomed out on the connecting ridge and cut down the the saddle proper before starting back up Alpamayo proper. It looked like the only areas we would need to place any protection would be the last two pitches as the first few steep sections were pretty tame.

We climbed to the top of the intermediate peak and crossed over another small bergshrund to the proper summit of Tarija. We stopped for a Goo and drink and now, in full sunlight, we looked down the class 4 scramble to the connecting ridge and Pequeno Alpamayo beyond. We knew the route from before and took the opportunity to drop the trekking poles and a few other gear items we knew we would not need. The climb down to the connecting ridge is straight forward and takes perhaps 15 minutes. We were not in a hurry but we did know that there was a group fairly close behind us and we knew we did not want to share the route with or follow another group up the flank of Alpamayo. We bottomed out on the connecting ridge and cut down the the saddle proper before starting back up Alpamayo proper. It looked like the only areas we would need to place any protection would be the last two pitches as the first few steep sections were pretty tame.  We climbed on an came to the bottom of the second to lat pitch which is the longest and I think the steepest part of the climb. G took the lead as my fecal interlude has taken most of the energy i had to spare. I was climbing and feeling OK but I was not lead material at this point of the climb. We looked at the pitch and G took the pickets and screws, as I would second. We both felt good enough to simul-climb the pitch, not seeing a need to set a formal belay but wanting to have a bit of gear in just in case. G took off, placing a screw down low to protect the base of the climb and then two pickets and another screw toward the top. We found that the neve was thin, real thin, and what lay under it was hard blue ice. We used all the protection we had to clear the top of that slope and really ended up climbing the top quarter with no gear in as I was grabbing the pro as I passed each piece so we could use it again on the next pitch. The top quarter was tamer so neither of us took serious worry over the lack of protection.

We climbed on an came to the bottom of the second to lat pitch which is the longest and I think the steepest part of the climb. G took the lead as my fecal interlude has taken most of the energy i had to spare. I was climbing and feeling OK but I was not lead material at this point of the climb. We looked at the pitch and G took the pickets and screws, as I would second. We both felt good enough to simul-climb the pitch, not seeing a need to set a formal belay but wanting to have a bit of gear in just in case. G took off, placing a screw down low to protect the base of the climb and then two pickets and another screw toward the top. We found that the neve was thin, real thin, and what lay under it was hard blue ice. We used all the protection we had to clear the top of that slope and really ended up climbing the top quarter with no gear in as I was grabbing the pro as I passed each piece so we could use it again on the next pitch. The top quarter was tamer so neither of us took serious worry over the lack of protection. We kept moving and went right into the next pitch, which was a full rope length, shorter than the the rope and half length of the first pitch. G beat his way up this one as well, breaking off dinner plate pieces of blue ice with every stick of his tool. I'm dodging the ice as it come down, learning all too well the moves I had inadvertently taught G on the Silverhorn route of Mount Athabasca in 2002 when we climbed a similar icy slope. The cramponing here is front pointing as the slope was too steep for me to use the french technique that i prefer in all cases. We topped the second slope and walked the final meters to the summit proper. I was beat but we were both on the summit and happy to be there.

We kept moving and went right into the next pitch, which was a full rope length, shorter than the the rope and half length of the first pitch. G beat his way up this one as well, breaking off dinner plate pieces of blue ice with every stick of his tool. I'm dodging the ice as it come down, learning all too well the moves I had inadvertently taught G on the Silverhorn route of Mount Athabasca in 2002 when we climbed a similar icy slope. The cramponing here is front pointing as the slope was too steep for me to use the french technique that i prefer in all cases. We topped the second slope and walked the final meters to the summit proper. I was beat but we were both on the summit and happy to be there. The following party, a gal from Washington State and a Bolivian guide topped out about ten minutes later and we took the obligatory summit shots for each other. I also took the opportunity to duck down the slope and make another deposit, like that was really a surprise. We shot a Goo, ate bit of the bag lunch Mario provided us with and prepared to head down. We figured to rappel the steep slopes, doing the second one in two pitches to land us on the flats at the bottom. We also found that if we trended a bit off to the side of the obvious route the neve was not beat up as badly. We set a picket for the first slope and G rappelled on down and took up a belay stance on the upper flat. i down climbed to him and we walked the lip of the longer pitch, set a picket and rappelled most of the way down. We set a second picket and rappelled and down climbed the bottom half, leaving one picket above for Pachamama or more likely the pair of pretty damn good Italian climbers who ascended past us, un-roped, as we came of the second pitch.

The following party, a gal from Washington State and a Bolivian guide topped out about ten minutes later and we took the obligatory summit shots for each other. I also took the opportunity to duck down the slope and make another deposit, like that was really a surprise. We shot a Goo, ate bit of the bag lunch Mario provided us with and prepared to head down. We figured to rappel the steep slopes, doing the second one in two pitches to land us on the flats at the bottom. We also found that if we trended a bit off to the side of the obvious route the neve was not beat up as badly. We set a picket for the first slope and G rappelled on down and took up a belay stance on the upper flat. i down climbed to him and we walked the lip of the longer pitch, set a picket and rappelled most of the way down. We set a second picket and rappelled and down climbed the bottom half, leaving one picket above for Pachamama or more likely the pair of pretty damn good Italian climbers who ascended past us, un-roped, as we came of the second pitch. We retraced our course across the connecting ridge and tried to make good time as the sun was quickly softening the snow and we wanted to stay ahead of lousy conditions on the main part of the glacier as much as possible. We trudged up the short climb to the base of the rock leading to the summit of Tarija and then climbed to that summit, not bothering to un-rope or drop our crampons. We reclaimed our trekking poles and other left luggage and made our way down the steep face of Tarija to the connecting saddle and circuitous route out and around the bergshrund and sole major crevasse on the whole climb. Then it was down the long slope to the toe of the glacier, a route we made good time on as we wanted to avoid any extended stops below the flank of Huayomen and the possibility of anything sliding from its sun scorched upper snow fields.

We retraced our course across the connecting ridge and tried to make good time as the sun was quickly softening the snow and we wanted to stay ahead of lousy conditions on the main part of the glacier as much as possible. We trudged up the short climb to the base of the rock leading to the summit of Tarija and then climbed to that summit, not bothering to un-rope or drop our crampons. We reclaimed our trekking poles and other left luggage and made our way down the steep face of Tarija to the connecting saddle and circuitous route out and around the bergshrund and sole major crevasse on the whole climb. Then it was down the long slope to the toe of the glacier, a route we made good time on as we wanted to avoid any extended stops below the flank of Huayomen and the possibility of anything sliding from its sun scorched upper snow fields.