|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Banff Assiniboine Expedition IAugust 6, 2002 – Two Screws Short of a Climb on Mount Aberdeen

The plan for the following morning was the same, up at three, breakfast in the RV and hit the trail by four for what promised to be a full day. Our climb of Mount Aberdeen would demonstrate that every climb on this trip would likely be a learning experience and even if not successful provide an opportunity to hone skills not yet practiced without the watchful eye of a guide. That is right, this was the first glacier climb for us without a guide but we were confident and ready for the challenge of not only getting ourselves to the summit but also handling any problems that might crop up enroute.

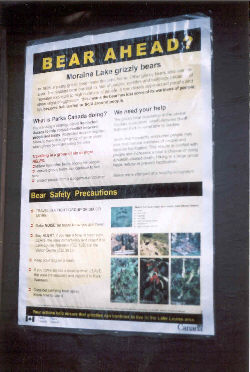

Our first challenge would be to get to the climb without encountering any of the larger local denizens known to haunt the Banff National Park, i.e. grizzly bears. Unlike Colorado, where in all my climbing I have yet to see a bear, this approach carried the distinct possibility of an encounter given the signs posted, the hour of our departure and suggestions by park officials that minimum parties of six travel tightly and noisily together. Gary had purchased pepper spray to carry along on the alpine starts but our main plan was lots of noise. For those readers who climb often in the company of the same group, this means cheerful banter based most likely upon some action by one member that was sufficiently different to make him the target of long-term abuse. Our walk in was no different.

The trail to Aberdeen leaves the Lake Louise upper parking lot and is signed for the saddle below Mount Fairview. The weather was cloudy but the rain seemed to be holding off so we were go for the climb. We followed the well-worn track to the saddle and then cut off on the spur trail toward Fairview. I had spoken with a ranger earlier with regard to the trail to Aberdeen proper and been advised that a slight climber’s path did depart from the Fairview trail and may even be marked with a cairn. We kept our eyes open and after one false alarm, spotted a cairn and a strong climber’s trail leading across the flank of Fairview, as described in the guidebook. We soon confirmed we were on track as the sun slowly rose to illuminate our route across the top of a hanging valley and onto a series of large moraines.

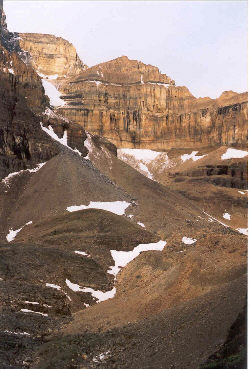

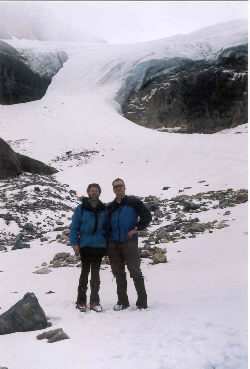

The moraines and some patchy snow led us to higher ground and a turn in the valley which once made, exposed the toe of the Aberdeen Glacier and the summits above. The glacier appeared to have receded since the guidebook photo was taken, but we had arrived and now the climb going to get real. The weather was still on our side as we stopped at the toe of the snow to gear up for the glacier travel to follow. We knew from our ranger discussion that the lower snowfield would not be crevassed but then we would need to climb an ice tongue that included a 60-degree bulge and the possibility of crevasses. Above the initial steep ice, the slope was reported to mellow before steepening again in an encounter with the bergshrund. The bergshrund would be turned on the climber’s left and the col separating the two summits would quickly follow. From the col, an easy hike up the snow would lead us to the summit of Aberdeen, and we could pick up Haddo on the way down if time allowed. Easy huh? We figured it would be . . .

We roped up using a 30-foot interval and Kiwi coils on the front and back ends. Gary took the lead and I the sweep as we climbed to the toe of the ice forming a frozen cascade over the first headwall. We had researched the Canadian Alpine Club’s accident summaries and knew that this slope was innocent looking but that it had abruptly put two parties into the rocks below, resulting in helicopter evacuations of climbers with broken limbs and internal injuries. The snow steepened and as we approached the tongue, the presence of hard ice below foot, masked only by three inches of loose snow, became evident. Our plan was to protect the climb using ice screws to set a balanced anchor and then run out a lead climber to establish the next stance and subsequently belay the following two climbers up the slope. Then we would leapfrog, sweep transitioning to lead, to efficiently climb the icy hump to the mellow ground above.

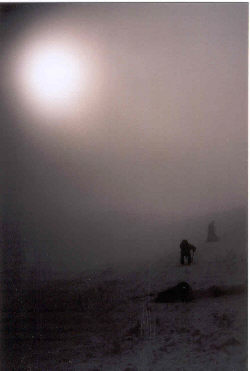

Well . . . things do not always work out as planned and we soon found that the ice was steeper than we anticipated and instead of settling for a mid point screw for protection, we would need two tools and three intermediates. Problem was, we did not have those two extra screws for the intermediate protection. We could have robbed one from the base or top stance but doing so would have precluded any balanced anchor or backup in the event of a leader fall. Had we been on similarly sloping snow, we would have been on more familiar ground from our Colorado experience but this was hard ice. To compound our concerns, the weather began to deteriorate rapidly and within minutes, we had gone from mostly sunny skies to steady snow and finally heavy fog and snow. At that point, we were two pitches up the three-pitch bulge with no visibility ahead or to the rear. Time to retreat.

The retreat was, however, as good an experience as the climb up to that point. We were not hurried and took time to practice lowering climbers to a lower stance from which they in turn could belay the leader on his descent. Two pitches later, all three of us were back at the base of the ice tongue from which we could make a more comfortable roped walking descent to the toe of the snowfield. The descent was of course not without incident. Firstly, I managed to pry off a dinner plate sized piece of ice with my second tool that subsequently hit Gary in the knee. Lesson: climb on the diagonal to protect the party below. To preclude a repeat, I moved on a diagonal to the right and managed to do what comes naturally to me, drop into a snow filled crevasse up to my waist. I planted the second tool to crawl back up over the lip . . . first Bolivia, now Canada. I have to give up this knack for finding crevasses.

We stepped off the snow and back onto the moraine before dropping our rope and packing the ice gear for the long walk out. The weather cleared, of course, and the sun once again came out but not without clouds nipping at it to confirm that our decision to turn the climb was proper. The long return still awaited us and we walked back into the tourist packed parking lot at 6:30 p.m., a 14-1/2 day or as they say in Canada, a “full” day. Lessons we learned on climb #1:

August 7, 2002 – Rest, Relocate, and EquipThe next climb planned was Mount Athabasca, located up to the north at the Columbia Icefields. We decided that a rest day was needed and that Gary and Diana would relocate the RV to the Campground near Athabasca and get two campsites, adjacent if possible. In the meantime, Jim and I would go south to Banff, stock up on groceries for the next three days and procure another couple of ice screws to adequately protect later climbs. Banff has pretty much anything one needs in the way of food or gear. We went to Monods on the main drag and picked up two BD 22cm screws and some other miscellaneous hardware that we learned from our Aberdeen climb would be required to safely and efficiently climb on steeper ice.

Jim and I caught lunch in Banff and dried some wet gear before heading for the Icefields on the southern border of Jasper National Park. We took the Icefields Parkway north, passing Bow Lake and Glacier and Mount Cheffren, which is one incredible looking alpine spire just begging to be climbed. Gary and Diana had been successful in their efforts as well and by late afternoon, we had established our camp for the next two nights in the Wilcox Creek campground. Our plan for the next day was another alpine start for the climb of Mount Athabasca. We stopped in the Icefields Center and registered our planned climb at the Park service counter. If one registers and then fails to call in at the given time, the Park’s rescue team is notified that a party is in trouble. Given that Diana was not climbing with us, but instead managing the base camp and that we had radios to communicate between the climbing team and base, there was little chance of our going late without notice . . . but we went through the process regardless. Most importantly, the conversation with the ranger generated an opportunity to read the comments in the climbing log, a justification of the process in its own right. Procedure satisfied, dinner eaten, and gear packed . . . three in the morning was going to arrive all to fast.

|