|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

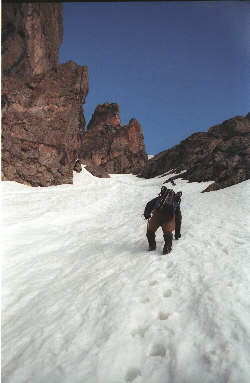

Chopicalqui - Millisraju ExpeditionExpedition Summary“Expedicion Sonia Morales II” was our return to Peru’s Cordillera Blanca (map) that aimed for two 6000-meter summits. Two summits that high in two weeks was a lofty goal but one bolstered, albeit tacitly, by the more realistic realization that if one summit was achieved, the trip would be a resounding success. Our goal was to climb Chopicalqui and then take a shot at Artisanraju, a climbing plan that allowed for no slippage, either in the logistical or acclimatization schedules. However, the glitch came eight weeks before we left, when a surgeon gently slipped my gallbladder out through a small incision. The “slippage” we sought to avoid, crept inexorably creep into the expedition schedule. We took a good shot at Chopi but without success, turning the climb just steps above the col camp at 18,500 feet. We attempted to salvage our “6000 meter” goal with a move to the Quebrada Santa Cruz for an attempt at Quitaraju. But it was simply not to be due to the condition of the ice field overhanging the approach to the Alpa Mayo/Quitaraju col. We threw the guidebook to the winds and made tracks to a more remote tributary valley and the summit of Millisraju, a/k/a Millishraju, a 5500 meter peak that offered a trackless route to a rarely visited summit and a spectacular view. Expedicion Sonia Morales was a success even though we never crossed the 6000-meter contour. We scored a rarely “couple times a season” summit, trekked 50 miles of trail in a new valley, had great local staff for company, and experienced alpine challenges that added to our growing climbing skills. We also turned the corner on guidebook based climbing as we discovered the experience of sorting out a route from afar, finding an approach, and making a climb that we would not have otherwise given thought to or taken the opportunity to complete. Like my other trip narratives, this report provides a detailed description of routes, logistics, and most importantly our sights and observations, not only on the climbs but also on our way to and from the Cordillera Blanca. I’m also going to mention that this trip, like others on this website, is an average Joe’s experience and not that of a group of mountain guides, hardcore climbers or stoked egos. I tell of our missteps, turnarounds, bad days, and failures, likely to the laughter of more experienced climbers but such will be the experience of other average climbers seeking to step up to climbs in the Cordillera Blanca or any other world class range. Most importantly this trip was not just a quest for summits but an adventure that took us from the daily routine of home and work to a foreign place where each day promises an experience different from the day before.

Trip Planning“American citizens traveling to or residing in Bolivia should be aware that various groups within Bolivia have conducted protests, demonstrations and blockages since May 16 to protest gas policy . . . The focus of the protests is La Paz and the surrounding Altiplano. While the La Paz airport, located on the Altiplano, remains open, some flights have been cancelled and others diverted. Travel from the airport to La Paz is subject to sporadic blockades. Roads running north and south from La Paz, to Lake Titicaca and Oruro, are blockaded and not open for travel . . . Travelers in vehicles should not attempt to pass through or around roadblocks, even if they appear unattended.” U.S. Embassy Website Travel Advisory, posted June 1, 2005. Peru was our planned back up and, given the unknowns associated with Bolivia, the Peru option was OK with us. We had climbed in the Cordillera Blanca the previous summer, found a great logistics provider and the odds favored of better weather than in 2004. We figured we could probably score two new peaks; however, we would be shy one member of our trio as Shart Strangelove was headed for a 450-mile canoe race down the Yukon River. Bolivia was out . . . Peru was in . . . so we contacted Chris Benway to see if he could cover the logistics. Chris was good to go and so we set about picking a pair of peaks for the two-week trip. In 2004, our plan was to acclimatize on Nevado Pisco (5752m, AD-) and then move across the valley to take a shot at Chopicalqui (6354m, AD). The weather robbed us of the opportunity in 2004 so it seemed logical to take a second shot at Chopi in 2005. The problem was that we did not want to repeat the Pisco climb to acclimatize and we did want to take a shot at Artesanraju in the adjoining Paron valley. The quandary was how to acclimatize and pull off a big peak right out of the gate. Our answer . . . do it slowly and model our ascent rate after the one that proved successful on Huyana Potosi a four years before in Bolivia. After Chopi we planned to head to Huaraz for a day of rest and then to the Paron valley to climb Artesanraju (6025m, D). Chopi, with or without success, was expected to complete the acclimatization process, giving us a good shot at Artesan. Should Artisanraju be out of condition, we would instead go to the Santa Cruz valley and take a shot at Quitaraju (6036m, AD). Following our second climb in either the Paron or Santa Cruz valley, we would be homeward bound. PreparationsTraining and Skill Development:

Last year’s Pisco climb demonstrated that our ice climbing skills were sufficient to overcome a 25-meter impediment . . . but that our style could bear improvement. We closed out 2004 with a day of waterfall ice climbing, just WI-2, but still a good opportunity to climb with a top rope and practice placing tools, feet and protection. We also achieved a January summit of Pagoda Mountain, one of the more remote mid 13k summits at the head of Glacier Gorge in Rocky Mountain National Park. The spring snow season that followed in Colorado was a combination of much snow and even more avalanche risk; regardless, we still managed to accomplish two steep snow climbs . . . even after the gallbladder affair. Following prior trips to Bolivia, Canada, Peru, and Colorado climbs, we have most of the gear we need. We replaced some older, heavier ‘biners by substituting wire gates and switching to lighter Spectra slings and cordelettes instead of heavier nylon gear. We also picked up some additional pickets for the steep snow routes on Artesan and Quitaraju. References:

The best book on the Cordillera Blanca is probably Brad Johnson’s guide. If you are not familiar with this reference, it is truly a beautiful book and provides details for a full range of peaks. I often look at this guide and even if you are not Peru bound, get a copy anyway . . . it’s great for the armchair climber. Bear in mind; however, that routes change over time so all may not be exactly as described. Also there is a lot of climbing in the Blanca that is not described in the guidebook. Maps: We used the Alpenvereinkarte North map of the Cordillera acquired for our trip last year. We found these maps readily available in Huaraz. And then there was my gallbladder . . .

With our departure date firmly set for July 1, I made a late April visit to a local surgeon and received his assessment of the condition of my gallbladder. “It needs to come out” was the opinion and that day I was scheduled to go under the knife on May 3rd. Not a lot of choice really, the gallbladder was packed with stones and the cutter’s prognosis for the outcome of a gallbladder attack at altitude was euphemistically stated as “poor.” The gallbladder came out on May 3rd. Though the surgery was performed as an outpatient procedure, it was, in the words of the surgeon, not a minor procedure. The gallbladder was in lousy shape, according to physician and pathologist alike, and had been going down hill for a number of years. The surgery stopped my pre-trip conditioning dead in its tracks for three weeks, after which I was cleared to climb again. G and I pulled off an 1800-foot snow climb in Rocky Mountain Park on May 21st and then another steep snow climb with a much longer approach two weeks later. I was also able to get back up to about 15 miles per day on my bicycle commute. My conditioning took a substantial blow and I did not fully recover by the time we headed south. My climbing partner was in great shape and ready for the altitude but he was teamed with a climber still tired inside and destined to remain a few steps behind for the entirety of the trip. |